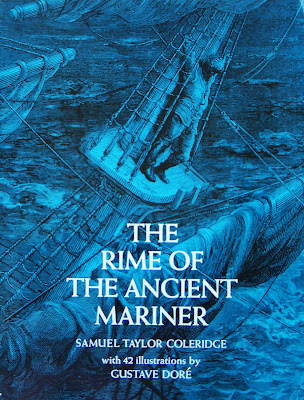

Montaigne. Dali´s illustration for Essays of Michel de Montaigne

[Charron has borrowed with unusual liberality from this and the

succeeding chapter. See Nodier, Questions, p. 206.]

"Scilicet ultima semper

Exspectanda dies homini est; dicique beatus

Ante obitum nemo supremaque funera debet."

["We should all look forward to our last day: no one can be called

happy till he is dead and buried."—Ovid, Met, iii. 135]

The very children know the story of King Croesus to this purpose, who being taken prisoner by Cyrus, and by him condemned to die, as he was going to execution cried out, "O Solon, Solon!" which being presently reported to Cyrus, and he sending to inquire of him what it meant, Croesus gave him to understand that he now found the teaching Solon had formerly given him true to his cost; which was, "That men, however fortune may smile upon them, could never be said to be happy till they had been seen to pass over the last day of their lives," by reason of the uncertainty and mutability of human things, which, upon very light and trivial occasions, are subject to be totally changed into a quite contrary condition. And so it was that Agesilaus made answer to one who was saying what a happy young man the King of Persia was, to come so young to so mighty a kingdom: "'Tis true," said he, "but neither was Priam unhappy at his years."—[Plutarch, Apothegms of the Lacedaemonians.]—In a short time, kings of Macedon, successors to that mighty Alexander, became joiners and scriveners at Rome; a tyrant of Sicily, a pedant at Corinth; a conqueror of one-half of the world and general of so many armies, a miserable suppliant to the rascally officers of a king of Egypt: so much did the prolongation of five or six months of life cost the great Pompey; and, in our fathers' days, Ludovico Sforza, the tenth Duke of Milan, whom all Italy had so long truckled under, was seen to die a wretched prisoner at Loches, but not till he had lived ten years in captivity,—[He was imprisoned by Louis XI. in an iron cage]— which was the worst part of his fortune. The fairest of all queens, —[Mary, Queen of Scots.]—widow to the greatest king in Europe, did she not come to die by the hand of an executioner? Unworthy and barbarous cruelty! And a thousand more examples there are of the same kind; for it seems that as storms and tempests have a malice against the proud and overtowering heights of our lofty buildings, there are also spirits above that are envious of the greatnesses here below:

"Usque adeo res humanas vis abdita quaedam

Obterit, et pulchros fasces, saevasque secures

Proculcare, ac ludibrio sibi habere videtur."

["So true it is that some occult power upsets human affairs, the

glittering fasces and the cruel axes spurns under foot, and seems to

make sport of them."—Lucretius, v. 1231.]

And it should seem, also, that Fortune sometimes lies in wait to surprise the last hour of our lives, to show the power she has, in a moment, to overthrow what she was so many years in building, making us cry out with Laberius:

"Nimirum hac die

Una plus vixi mihi, quam vivendum fuit."

["I have lived longer by this one day than I should have

done."—Macrobius, ii. 7.]

And, in this sense, this good advice of Solon may reasonably be taken; but he, being a philosopher (with which sort of men the favours and disgraces of Fortune stand for nothing, either to the making a man happy or unhappy, and with whom grandeurs and powers are accidents of a quality almost indifferent) I am apt to think that he had some further aim, and that his meaning was, that the very felicity of life itself, which depends upon the tranquillity and contentment of a well-descended spirit, and the resolution and assurance of a well-ordered soul, ought never to be attributed to any man till he has first been seen to play the last, and, doubtless, the hardest act of his part. There may be disguise and dissimulation in all the rest: where these fine philosophical discourses are only put on, and where accident, not touching us to the quick, gives us leisure to maintain the same gravity of aspect; but, in this last scene of death, there is no more counterfeiting: we must speak out plain, and discover what there is of good and clean in the bottom of the pot,

"Nam vera; voces turn demum pectore ab imo

Ejiciuntur; et eripitur persona, manet res."

["Then at last truth issues from the heart; the visor's gone,

the man remains."—Lucretius, iii. 57.]

Wherefore, at this last, all the other actions of our life ought to be tried and sifted: 'tis the master-day, 'tis the day that is judge of all the rest, "'tis the day," says one of the ancients,—[Seneca, Ep., 102]— "that must be judge of all my foregoing years." To death do I refer the assay of the fruit of all my studies: we shall then see whether my discourses came only from my mouth or from my heart. I have seen many by their death give a good or an ill repute to their whole life. Scipio, the father-in-law of Pompey, in dying, well removed the ill opinion that till then every one had conceived of him. Epaminondas being asked which of the three he had in greatest esteem, Chabrias, Iphicrates, or himself. "You must first see us die," said he, "before that question can be resolved."—[Plutarch, Apoth.]—And, in truth, he would infinitely wrong that man who would weigh him without the honour and grandeur of his end.

God has ordered all things as it has best pleased Him; but I have, in my time, seen three of the most execrable persons that ever I knew in all manner of abominable living, and the most infamous to boot, who all died a very regular death, and in all circumstances composed, even to perfection. There are brave and fortunate deaths: I have seen death cut the thread of the progress of a prodigious advancement, and in the height and flower of its increase, of a certain person,—[Montaigne doubtless refers to his friend Etienne de la Boetie, at whose death in 1563 he was present.]—with so glorious an end that, in my opinion, his ambitious and generous designs had nothing in them so high and great as their interruption. He arrived, without completing his course, at the place to which his ambition aimed, with greater glory than he could either have hoped or desired, anticipating by his fall the name and power to which he aspired in perfecting his career. In the judgment I make of another man's life, I always observe how he carried himself at his death; and the principal concern I have for my own is that I may die well—that is, patiently and tranquilly.

ESSAYS OF MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE